- Home

- Hannah Robert

Baby Lost

Baby Lost Read online

‘Heartbreaking, powerful, clear-sighted. Powered by the clarity and force of a mother’s great love for her children, and the author’s reflective capacity honed by years of legal practice and research, this memoir faces fundamental questions about life itself. Hannah Robert experienced an immense tragedy and has given others a true and guiding light.’

Zoë Morrison

‘Hannah Robert’s Baby Lost is a stunning rumination on the minutiae of loss and grief, and the epic struggle involved in putting yourself back together after unspeakable tragedy.

Baby Lost is a courageous and beautiful memoir. With devastating honesty, Hannah offers up her grief, presenting her story with a deft, insightful touch, allowing the reader to bear witness to a loss that is far too often unspoken.’

Monica Dux

‘A gutsy, vivid and unflinching book about unspeakable loss. Hannah Roberts’s book will resonate with anyone who has known the darkness of grief, and the gradually returning light.’

Hilary Harper

baby

lost

baby

lost

A story of grief and hope

HANNAH ROBERT

MELBOURNE UNIVERSITY PRESS

An imprint of Melbourne University Publishing Limited

Level 1, 715 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia

[email protected]

www.mup.com.au

First published 2017

Text © Hannah Robert, 2017

Design and typography © Melbourne University Publishing Limited, 2017

This book is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 and subsequent amendments, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means or process whatsoever without the prior written permission of the publishers.

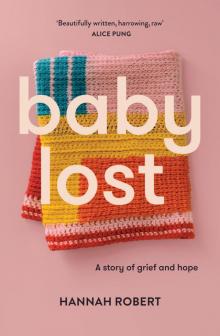

Lyrics by Katy Steele (Little Birdy) are reproduced with permission, via Graham McLuskie. Extracts from ‘When Things Fall Apart’ by Pema Chödrön are reproduced with permission, courtesy of the Pema Chödrön Foundation. Zainab’s blanket, pictured on the cover, was knitted and crocheted by Joanna Robert.

Every attempt has been made to locate the copyright holders for material quoted in this book. Any person or organisation that may have been overlooked or misattributed may contact the publisher.

Text design and typesetting by Cannon Typesetting

Cover design by Klarissa Pfisterer

Printed in Australia by McPherson’s Printing Group

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry

Robert, Hannah, author.

Baby lost: a story of grief and hope/Hannah Robert.

9780522869439 (paperback)

9780522869446 (ebook)

Robert, Hannah.

Mothers—Australia.

Fetal death—Psychological aspects.

Grief in women.

Hope.

If the content of this book brings up issues for readers, for help or information call: SANDS (Stillbirth and Neonatal Death Support): www.sands.org.au

Stillbirth Foundation (A charity raising money for research and education on stillbirth and stillbirth prevention): stillbirthfoundation.org.au

An online community of baby lost parents, which includes resources on how to plan a funeral for a baby, how to help a friend through baby loss etc.: www.glowinthewoods.com Lifeline: 131 114

Contents

Part I: Impact

1 Sunday, 27 December 2009

2 The second-best blanket

3 Shavasana

4 The torture booties

5 The crazy lady in ward four

6 Frida and me

7 Tabloid tragedy

8 Permission to bend

Part II: Re-entry

9 Zombieland

10 The ‘born alive’ rule

11 Sun salute with bedpan

12 The posthumous godfather

13 Matryoshka

14 Histopathology

15 Proof

16 Scar tissue

17 Funeral appreciation

18 I have a dark-haired daughter

19 Dr No-Sperm-for-You

20 Heartbeat

21 Making the judge cry

22 Close up with hope

23 The charnel ground

24 Fat Tuesday

25 Undone

26 Tsunami

27 Earth and sun

Part III: Ripples

28 Both my babies

29 Zoe’s Law

30 Holding the torch

Acknowledgements

Notes

For Zainab and Mia and all the other babies gone too soon

Promises

I will greet you with hands smelling of oranges.

I will kiss your mouth in your sleep.

I will let you surprise me

Over and over again.

I will curse that my hands can’t bat away all the things that will hurt you.

I will remember—despite the shock—that no matter how many times I have dreamt you

You are your very own dream

From your very own flickering head.

I will breathe you in and mingle you with my familiar cells.

I will breathe you out and let you mingle amongst the hard and soft particles of the air.

I will bring you home,

And I will open the door.

And as much as I delight

In the still unreal thought

of seeing the light bounce

from your face onto mine

I will not hurry you.

(September 2009)

Part I

IMPACT

1

Sunday, 27 December 2009

There is only one place to start with this story—the point where all the ripples start, the moment of impact. Everything circles around that.

I replay this moment often. There we were, buckled in and travelling north on a suburban arterial road at around 5.40 p.m. two days after Christmas. We were not a conventional family for all kinds of reasons—two mums (one Lebanese, Rima; one a ‘skip’, me), with Rima’s teenage daughters from her previous marriage (Jackie and Jasmin), and our long-awaited donor-conceived baby on the way—but it was the most ordinary of family car trips. We were heading home in the station wagon after visiting my cousin to drop off belated Christmas presents. I was driving, with Rima next to me in the front passenger seat; Jasmin in the back seat on the left, reading her book; and Jackie behind me. She had been leaning on the window gazing out, but leaned forward to ask Rima something.

We’d been listening to the cricket, and I said to Rima, ‘Hon, can we change this? Listen to some classical music for Haloumi?’ Haloumi was our name for the baby that bulged in my eight-months pregnant belly, that had been hiccuping all morning.

But Rima didn’t reply, and didn’t change the station, because in front of us we could see exactly what this moment was—in the shape of a four-wheel drive, which had hit the car in front of it in the southbound lane and was now swinging sideways onto our side of the road. I’d started an annoyed query, ‘What is he doing?’, but finished with a yell, ‘FUCK OFF!!’

And I braked. I pushed with my arms and my legs, and the tiny hairs on my arms and legs, to try to push that car away from my family and me, and the little one curled in my belly.

The impact smacked two moments—before, and after—together so forcefully that I was left puzzling about what they were doing next to one another. All I know of it was its loudness, and the shudder it left in our bones. We know it happened, we had the evidence before us, in torn metal pieces and CT scans, but it was too quick—too much to fit into one tiny moment, so that everything broke, and the normal boundaries of our lives split apart.

We stopped moving instantly and I could still hear myself yelling and thought, ‘Too late for that,’ and shut my mouth so hard that my teeth chipped against one another. I made a decision—this was actually happening, and since I couldn’t undo it, I’d better deal with it.

I turned the engine off and looked at Rima—lovely, alive Rima, though she was screaming too by now. I could hear the girls screaming behind us, and though I couldn’t turn and see them, I knew they would be hurt but okay.

I looked to my right, where the four-wheel drive had come to a stop, as if we were just parked cars in some wrecking yard. A clear liquid was gushing from the other car’s mangled engine. I thought, ‘If that’s petrol, we could be blowing up any moment now.’ I had visions of an action-movie scene—a billow of flame, and bodies moving in slow motion. I couldn’t move—the car was crushed in around my legs. ‘Rima, get out of the car. Tell the girls to get out.’

Later, in the hospital, Rima mused, ‘I opened the car door, but then I realised I was too hurt to actually move. Why did I open the car door?’

‘Because I told you to get out. Because I thought the car would explode.’

I felt calm. I drew great draughts of air and tried to send some of that calmness towards Rima, who was still screaming. My thoughts sliced through the slow-moving time around us. If we could just be calm and reasonable, it would all be okay—the ambulances would come, they would unfold this car around me, my baby might have to arrive a little early but would be okay. Thirty-four weeks—this child would already be so strong. ‘Viable’. Isn’t that right, Haloumi?

•

Seven months before, on a Friday night, I had got off the train from Newcastle, and walked up the hill from Central Station in Sydney’s gritty heart and into the pub where Rima was having work drinks.

‘Hannah!’ Nan and Veronica beamed at me, arms open. ‘Here she is!’ Rima turned and gave me a bigger smile and a tighter squeeze than usual. And then, in my ear, ‘You still feeling nauseous?’

‘Yep—still queasy.’

‘Good—I’ll get you a lemonade then!’

We hugged our secret to ourselves; it was still early days. But we were each allowed to tell one person, and Rima’s was Chantal. She found us later that evening, gave me a big hug and whispered, ‘So! I hear there’s a Mazloumi-haloumi on the way! A baby haloumi!’

I bit my lip and a smile split across my face. ‘Yeah—just a tiny little haloumi cheese so far, but definitely a little haloumi!’

I made cryptic Facebook posts: ‘I love haloumi cheese’ or ‘haloumi in my belly!’ I fretted about the logistics. Two-and-a-half years before, I’d made the leap from commercial litigator to lecturer at Newcastle Law School—I loved my work, but commuting from Sydney was complicated. I’d just received an offer to move to La Trobe Law School in Melbourne, where I’d grown up, and where my family would be close by. We’d decided on a move, but there was nothing simple about uprooting ourselves.

•

Where the impact had strangely calmed me, it had done the opposite to Rima. She was sobbing, ‘My children, my children.’ I held her hand; ‘Habibi, please, we are going to be okay.’

‘Can you feel the baby move?’ She looked at me hard, and asked the question again. I didn’t want to answer and engage with the universe of doubt that surrounded it.

‘I don’t know, my love. I’ve got a few other issues to think about right now.’

I listed these in my head, concisely and calmly: explosion, being cut out of the car, whether my legs or spine were crushed, Jackie, Jasmin. Inside my body felt calm, safe—it was the outside that was in trouble. Don’t worry, Haloumi, I’ll get us out of here.

•

When we sat in the obstetrician’s office six weeks later for our review appointment, I asked him about the heartbeat the paramedic said he had heard in the ambulance. ‘Is there anything on my file about that? Could she still have been alive in the ambulance?’

It took a good twenty minutes on the phone for him to get to talk to the person in charge of the medical records department.

‘There’s nothing on your file about a fetal heartbeat of 155 in the ambulance. We’ll probably never know, but I have to say it took me many years of practice as an obstetrician before I could accurately measure a fetal heartbeat with a stethoscope, so there’s a good chance they got it wrong. And, from the look of your placenta when we did the caesar, it had completely abrupted, probably very quickly on impact.’

I sat there looking at the dots on his bow tie and wished I could slap my coolly calm self as she sat in that wrecked car and say, ‘Your child is dying right now—anything you want to say to her, you need to say it now.’

•

In that calm space, it didn’t take long for people to come to us. A man appeared at my window. ‘I’m thirty-four weeks pregnant,’ I told him matter-of-factly.

He said, ‘Here, hold this to your head,’ and put a cloth in my hand, pressing it against the side of my head above my right ear. It didn’t hurt there; it was just warm and wet. He was already on the phone. ‘Two women, one of them is thirty-four weeks pregnant’—looking at me for confirmation.

I nodded.

‘Are you in pain?’

‘I’m okay; I just feel squashed. I can move my toes but I can’t get my legs out. I need to be cut out of here.’

I looked down—my legs were pulled up protectively around my bulging belly, my toes flexed a bit further back than I had thought possible. Metal and plastic were bent around my legs, but they felt whole and okay, just trapped. My toes were obediently wiggling—painted toenails (for Christmas), new bronze metallic Birkenstocks bent at angles. ‘I’ll have to get new Birkenstocks,’ I thought.

He kept moving around the car, relaying Rima’s injuries to the operator, then Jasmin’s, then Jackie’s. Another guy, younger, came to my door. ‘Are you okay?’ he started, and then said, ‘Oh fuck.’ I could feel the panic sweating off him as he looked at me and the car bent around me. I turned away and looked at Rima instead, letting my calm roll towards her.

•

In the trauma ward afterwards, I listened over and over to a particular song by Little Birdy:

I haven’t seen no place like this

I haven’t seen no place like this

No one will see, no one will see, what I do now, what I do now, oh it’s just us moving

I haven’t seen a place so ghost-like

a place that’s seen some of the best in my eyes

Pages will turn, sirens will sing, words will be said, words that will hurt,

oh it’s just us drifting

I was stuck there, drifting mid-impact, in the moment where my daughter’s whole lifetime folded concertina-like into nothing, where she became a ghost, and perhaps I did too. My body suddenly contained life and death at the same time, like babushka dolls nestled within one another. In that eerie place, the sound of ambulance and fire engine sirens is stuck on repeat; time stretched out, to create a new reality, abruptly disjointed from our previous one.

The first time I heard sirens after being released from hospital, my body shook with sobs before I could register what was happening. The taste of nausea on my tongue, a feeling of my blood draining out through my legs, my stomach dropping sideways.

•

In the time it took for the paramedics to come, for the firefighters to bring the giant can opener to release me from the car, I breathed. I held Rima’s hand until the paramedics took her, and then one of the firefighters got in her seat and held my hand. ‘You’re an ideal patient—very calm,’ he said.

‘I don’t see any point in making this worse,’ I replied. We didn’t really need to make small talk. The others were working hard, concentrating on bending the metal without hurting my soft body. I kept my hand on my belly—Come on, Haloumi, stay with me, little one.

•

I was fierce about our little family; for so many years, I hadn’t allowed myself to think it was po

ssible. As a teenager, I’d stood in my school uniform at the tram stop, radiating shame as I thought about the dream that had woken me that morning. I’d dreamt I was struggling with a snake that grew bigger and bigger, and at the very moment I thought it would constrict me, it became a woman, and the struggle changed into something else, which made me gasp because it felt so incredibly good. Oh no, I said silently, solemnly, to the mannequins in the shop window. I must be one of them. I couldn’t even say the word ‘lesbian’ in my head. It was a taunt, an insult hurled after all the others had been exhausted. The worst of the worst. At the school I went to, you might as well tattoo ‘Bully me’ on your forehead if you were going to admit to anything but vociferous heterosexuality.

I’d had boyfriends, and genuinely loved, and sometimes desired, them. That was how I could recognise the power of these feelings and responses—though they had a distinctly different social value. Having a boyfriend had won me a level of acceptance, of approval; the feeling of growing up how I was supposed to grow up. These feelings, though, threatened to mark me out, to contaminate me as abnormal, unacceptable, clearly destined for a sad, lonely, embarrassing existence. No one I knew was in a same-sex relationship—not a cousin, teacher, family friend, no one on any of the TV shows or films I’d seen. (No, that’s not quite true, there was the gay lawyer in Philadelphia, who died.) I knew people ‘like that’ existed, but in a universe so shadowy and far from my own that I had no desire to go there. Yet, that morning at the tram stop, I confronted the solemn knowledge that wherever that universe was, I was already an expatriate citizen whether I liked it or not. And the fact that I was having this imaginary conversation with womanly mannequins wearing foundation garments (no racy lingerie for Camberwell shop windows, thank you!) was only further proof of my guilt.

Fast-forward several years, to university, and I was having a very different conversation, at least with a live, human woman this time.

‘Have you ever been in love?’ she asked.

We were making noodles (literally, not metaphorically, I’m afraid) in her room at college. This was what happened after beers and dancing if we didn’t a) pass out or b) pick up boys. I preferred option c), even if I had to run the risk of a) or b) to make it a possibility.

Baby Lost

Baby Lost