- Home

- Hannah Robert

Baby Lost Page 10

Baby Lost Read online

Page 10

The book was The Brothers Lionheart by Astrid Lindgren—it still rates as one of my favourite books of all time. It didn’t strike me until recently that perhaps a book that starts with two little boys dying might be considered morose reading for a seven year old in hospital. But it wasn’t morose, not in the least, because dying was just the kicking-off point for marvellous adventures for these kids, in a world where they could fight dragons, and lead revolutions, and learn that sometimes, even people you loved failed you. This wasn’t ‘heaven’ and it certainly wasn’t a cushy affair with clouds, harps and eternal life. In my pink pyjamas and with my seven-year-old certainty, I wasn’t scared of dying, and I didn’t find out until years later what a close thing it had been, for a moment there. But when my grandparents died, I thought of them as there, in Astrid Lindgren’s Nangijala, going on with their slightly more adventurous lives and sending us a dove every now and then.

I hit a snag, though, in another hospital room twenty-six years later, when the buzz of medical people doing things to various remote parts of me had stopped at last, and I was left alone, and with-it enough, to think for the first time since the accident. My belly was still so swollen, but not with Z—so where was she? We’d just farewelled her cold little face, so where was my moving, hiccuping baby? What exactly did I believe happened after death? Rubber, meet Road.

I’d been to Sunday school and to church with my parents for a short period, but none of it rang true for me. If I had to sit through a Christian service, I would find myself going in argumentative circles in my head. So if I couldn’t bring myself to believe in heaven or hell, could I believe in Nangijala? Another life, just as mortal and complex as our own, with some familiar characters but different props? It seemed to work okay for my grandparents, but what about Z? She was too small for adventures, too small for riding horses and fighting dragons. She was still too small to be away from me and my heartbeat, or even to know how the whole communication-via-doves thing works. If small babies have trouble knowing that their parents still exist when they play peek-a-boo, then what hope did Z have of knowing how much we loved her, stranded as she was from us by death?

All I could think of was her wailing, in a rustic-looking basket on someone’s stone doorstep, and her little hands searching, and rustling the swaddling clothes. Someone would come, of course, but who? Some anonymous pre-modern wet nurse? I couldn’t work out which was worse—to think of her annihilated and stopped forever, or to think of her continuing on without us, lost and disconnected. Both scenarios made me howl and choke.

This was why I had to invent the idea of godparents, to populate her imaginary world with people we loved, who knew us and who could tell her how much we loved her, who could sort out doves for her. It kind of worked, but it still felt like an invention, a delusion to make things feel okay. And it still tore my heart to imagine her crying, and not being able to pick her up.

The week after I had been released from rehab, I sat down to write my rather odd letter to Joan Philips, the mother of the late David Philips, who had supervised my master’s thesis, and who had employed me in the history department for four years as a sessional tutor while I was finishing my MA and law degree. David was South African. After doing his first degree, at the University of Witwatersrand, he’d won a Rhodes Scholarship to study for his PhD at Oxford. He was passionately involved in the anti-apartheid movement and decided he did not want to return to South Africa while that regime prevailed. So he took a job at the University of Melbourne, where (a couple of decades on) I encountered him in a first-year subject on comparative colonial history. He was an imposing man—an associate professor by that stage—and he unapologetically took up space both physically and intellectually, and demanded that you, in turn, stand your ground and explain your position. He was fierce, but funny and good hearted. In a year when I was heartbroken from breaking up with my first girlfriend, David and my co-supervisor, Pat Grimshaw, helped me refocus on the thesis and get it written.

In August 2008, David had just retired, and was on holiday in Broome, when he died suddenly of a heart attack. Rosalind Hearder, a friend and colleague who’d taught with David and me, called. I was delighted to hear from her, but when I heard her tone, my heart dropped. It hadn’t occurred to me that David wouldn’t be here forever, and there were so many things I’d neglected to tell him. Rosalind and I asked David’s family if we could attend his funeral, and offered to say something on behalf of his students and university colleagues. David’s mother, Joan, welcomed us, and so we went along to the funeral, and spoke briefly about David and his significant impact on our lives and the lives of his students and colleagues.

Eighteen months later, the January after our accident, I was thinking a lot about David. He appeared in one of my dreams, in the crowds outside Shea Stadium in New York, which we’d visited in the months after he died. I was shocked to see him and said, ‘David, I thought you were dead.’ He guffawed at the idea and said, in his characteristic style, ‘Hannah, you are clearly incorrect!’

Joan wrote back, giving her blessing for us to appoint David as a posthumous godfather to our daughter, and recommending we go see the movie Invictus, which she thought he would have loved. The night before the memorial, I dug through the filing cabinet in the garage to find a page with his handwriting on it—the first page of the final draft of my master’s thesis. Seeing his lead-pencil handwriting, I blinked. I could see his office; I’d always have to move a pile of books so I could lean my notepad on the desk to take notes during our meetings.

We took the page with us to Somers. There, my dad folded it into a paper aeroplane and gave it several maiden flights before the service, when we buried it with Z’s ashes.

•

For a while after the memorial, the sadness made me paper-thin. Just breathing, opening my eyes and looking at my surviving loved ones felt so hard. I was glad of the automatic breathing reflex, because I certainly couldn’t have bothered doing it consciously. The rich smell of lillies pervaded our house. Not everyone had got the ‘no flowers, just donate to Oxfam’ memo, and I couldn’t just throw them out. They were beautiful. They were tangible expressions of love and sorrow. But watching them open, spill their pollen and slowly die, was less heartwarming. Still life, indeed. We’d had enough of that.

The memorial was hard but good—in a painfully satisfying way. We felt so loved, by everyone who came, and by everyone who didn’t come but sent messages or cards. It felt strangely like a wedding (perhaps because my dad and stepmum got married there nearly twelve years before), except for the volume of the weeping. We may not have been allowed our own wedding in this country, but Rima and I were now wedded in this grief.

An hour before the service started, I left things in everyone else’s hands and hobbled off to the beach with Rima, my sister and my brother. Jez and I went in the water—him rapidly, like an otter (his stubbly beard adding to the otter impression), and me slowly, letting the water lap its way up my broken body. It was warmer than usual, crystal clear and with very little seaweed.

I dived down and opened my eyes, feeling for the bottom with my hands. I came up, rolled onto my back and let myself float. How many days and hours since I last did that—but in the ocean baths in Sydney, and with Haloumi also floating inside me? And I thought of the spectacle I presented then, with my belly popping above the water like a fleshy island. The girls had thought it was hilarious when I took them to the pool and did backstroke; my belly sinking and rising with each stroke.

Now my fleshy island was just a wrinkly belly below the surface. I sobbed and let my tears mingle with the big, salty sorrow of the sea.

And, as always happens when I float like that, I realised that I’d stopped being aware of time, and was startled back into myself. When I opened my eyes and rolled over, Jez was floating right there beside me.

Somehow, time disappeared and, although we’d arrived about two hours early, we didn’t get a chance to test the music system, with the resu

lt that none of the music played properly. We would get the first few stanzas, and then it flickered in and out and was awful to hear. The songs I’d listened to on repeat in the hospital, which had come to feel as if they were written about us and our loss, were reduced to crackling static and snatches of a tune. I was cranky about it, but Rima was philosophical and calmed me with little pats on the arm.

Afterwards, we dried our salty cheeks as we walked back from the bush chapel, and ate and laughed and hugged people we hadn’t seen for months. I had made platters and platters of haloumi and zucchini fritters. The zucchinis had gone crazy in the vegie patch we’d inherited from our tenants. A friend had asked, half-seriously, while I was still in hospital, ‘Does this mean you can never eat haloumi again? Because it will be kind of like eating her?’

‘No, no,’ I’d chided. ‘We will eat it in remembrance of her!’

The next day, there were plates of the remaining haloumi zucchini fritters in the fridge. I didn’t want to throw them out; doing so felt sacrilegious. Our friends and family had gone home with full bellies and sore eyes, and now this leftover grief was ours to continue eating, day after day, magically renewed every time we finished it, like a weepy magical pudding.

An old friend who lived interstate called—could she come and visit? Was it okay if she brought her baby daughter?

People had been extra thoughtful about not bringing babies into our presence, as though I might be allergic to them. ‘No, please bring her. That would be lovely.’

She did, and the minute she walked in the door, asked, ‘Do you want to hold her?’ I did, and we looked at the pictures of Z and talked, while fat tears dropped onto her baby’s wispy head.

13

Matryoshka

On the one-month anniversary of the accident, Rima and I were at the doctor’s again. Our GP, Kelvin, was our new best friend in Melbourne. We’d picked an inner-suburban clinic that friends had recommended as LGBTI-friendly. None of the lesbian doctors we asked about were taking on new patients, so we reluctantly made an appointment with one of the male doctors. I presumed that he’d be expert on sexual health and drug interactions, but perhaps not so comfortable dealing with ‘women’s issues’—and we had plenty of those.

At the first appointment, though, Kelvin didn’t bat an eyelid. He sat and listened as we gave him the matter-of-fact version of the accident, paying compassionate attention, but not reacting. Then he offered help with the pragmatics of referrals, prescriptions and insurance certificates. He quickly became expert at summing up our story in a sentence or less; and navigating the bureaucracy of the three hospitals we’d had to deal with, as well as the government insurer who covered all vehicle accidents. This time, he was on the phone to the histopathology department at Royal Melbourne, on the Trail of the Disappearing Placenta.

Not much of Z’s birth had gone to plan, but the one request the midwives had thought they could help with was to keep Z’s placenta, so that we could bury it under a tree. A tree with a transient body part buried under it was a lousy substitute for a daughter, but it was something. Or it would have been, if only we could convince the histopathologist to give us back the placenta.

While Kelvin was on the phone, Rima found a set of nested matryoshka dolls in the toy basket. She looked at me, opened the first doll, and made her goofy ‘Surprise!’ face as she pulled out the next doll, making me smile. She opened the next and the next. There was surprise all the way down, until, ‘Ohhhhh’—sad face—when the last, tiniest doll could not open. The last of the line. My silent giggle turned into a sad face too, and I thought, ‘I don’t want to be that doll.’

On my next trip to the doctor, I discovered a hobby shop within hobbling-on-crutches distance, and bought several slabs of balsa wood and a small set of tools, so I could start whittling my own morose matryoshka set. The first and biggest doll was not a doll at all, but our car post impact, the front driver’s corner crushed in. Our car had been a Nimbus, a puffy little white cloud of a station wagon with Tardis-like properties. I hollowed out four spots inside, for Rima, Jac, Jas and me, and made small dolls for each of us. And then I hollowed out my own rounded doll, and made a tiny one to fit inside. It was harder than I’d thought. My whittling skills were pretty ordinary and the balsa did not behave as I expected it to. It was probably the wrong kind of wood. But there it was—a chunky wooden approximation of our wrecked car, with us wrecked inside it, and our daughter, the most terminally wrecked of all, inside me.

I made a little black-bordered birth announcement card, with an open matryoshka doll in one corner, the two empty halves leaning against one another. She had a sweepy fringe like mine and a chubby tear rolling down her cheek. In the opposite corner was a tightly swaddled dark-haired babushka baby, long eyelashes resting on her cheeks. A thick black border connected the two. We had the cards printed with Z’s name, weight, length, date of birth and a message in the centre. I had grand plans of sending them out to all the friends and family who had visited, helped and sent us cards, flowers and love, but every time I got out the list, I only managed a few before it all just felt too, too sad.

My Aunty Connie came to see us. When I was eleven, and her son was thirteen, he killed himself with a handgun—whether by accident or not, we’ll never know. She was blunt. ‘Your life is split now,’ she said. ‘There’ll always be before, and …’, she sighed, ‘… after.’ I imagined the bit in between as a gaping chasm, so that reminders of before felt like stranded relics, completely irrelevant and alien in their new setting. Not only my clothes, and our things as we gradually unpacked, but even songs on the radio. Books did not pass through my hands without me flipping to the front to find the publication date, so I could work out if it was a naïve resident of ‘before’, or a wiser, sadder survivor of ‘after’.

Tuesday, 16 February 2010

I visited the dentist this morning to have my front teeth repaired. They’d been chipped in the accident, when my jaws banged together like a nutcracker puppet. I’m usually one of those strange people who quite likes visiting the dentist, but today, holding my mouth open and seeing the dentist work above me, I was suddenly back in the ER, clothes sliced off and my body pinned down to the spinal board like a prize butterfly in a neck brace—a disinterested observer to the workplace that was my body.

Now my teeth are dulled again—the sharpness of chipped edges no longer catching on my tongue. I feel dulled too—shell shocked. The bomb has gone off—a good seven and a half weeks ago, and I’m still stunned, staring into space.

If I were a chimpanzee in the zoo, today would be the day I would spend with a blanket on my head, occasionally hitting myself (and others, if they came near) with a small tree branch. The equivalent human behaviour is staying in bed and eating 70% cacao chocolate, while listening to 90s grunge pop. Friends have made mixtapes for us—I played these and made my own lists to include the lyrics which echoed around my head about the ‘saddest summer ever’ and ‘help I’m alive, my heart keeps beating like a hammer’.

After the dentist, we went back to the hospital to meet with the same bow-tied obstetrician who had told us Haloumi had died. It was as though the movie was over and we were chatting with one of the actors on how the movie played out—reflecting on the motivations and plot, the ‘makings of’.

I feel slowed. I still don’t get it. There were women walking out of the hospital with babies tinier than mine. Living, breathing babies. Some with less hair than mine, some with more. Where is my baby? Where is she? Why can’t she be here in my arms? Why can’t we be fussing over her carseat so we can take her home? I know these thoughts are not productive, whatever that means. I still want to know. I was that close to having a living child in my arms.

I dreamt that I was at Z’s memorial service again, but I was riding a child’s ride-on toy. It was too small and whenever I stopped moving it would slide out from under me and ignominiously dump my bottom on the ground. A work colleague was there and remarked, ‘Oh Hannah! So good

to see you getting around!’

In another dream, I was cutting rosebuds, each with a dead rosehead in the centre. In another, I had to walk through a pool of shining wet eels, a dark slithering against my skin. Things were lost, landscapes disoriented, obstacles stood in my way. I had another baby and she lived, but I couldn’t remember her date of birth. Was she Z’s twin? Or had another whole pregnancy elapsed within seven weeks?

The other night I dreamt that I walked into a Victorian terrace house. A slick-looking bloke put his hands together in greeting: ‘It’s already started but what I’d suggest is that you join in with the group upstairs.’ I could hear voices raised and chairs pushed across the floor in the room above. Before I could climb the stairs, he caught my sleeve: ‘The scenario is—it is 1939 and you are requested to go on a secret mission to get sixteen European leaders to sign a pact undermining the Treaty of Warsaw, pre-empting it and giving them an out.’

It didn’t make sense to me. I felt foolish—I didn’t know enough to ask a meaningful question.

‘The main obstacle is this Austrian bloke who wouldn’t sign because he’d been circumcised.’

‘Circumcised? What did that have to do with it?’

‘He objects to the subterfuge. He wants it all out in the open. We need to convince him …’, he looked at me meaningfully, ‘… that this is the only way’.

I wanted to ask why, but he’s gone, and there are stairs I must climb.

It is chaos upstairs. I’m frightened. I know this is pretend, but it feels like a very serious sort of pretend.

I was still waking at 4 a.m. most nights. The sadness would ball up in my stomach so much that I wanted to throw it up, to get it out of my system so I could somehow go back to the land of ‘before’. I could see now the appeal in imagining things like this as being punishment by a vengeful god. Once you are punished, the balance is levelled and you can’t be punished again for it—apparently even God operates under a concept of double jeopardy. But if it’s not punishment, if it’s all random universal cruelty, then it could happen again at any time, and to anyone I love.

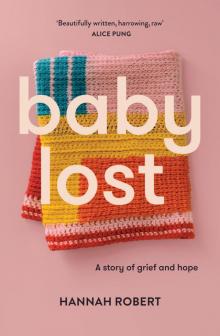

Baby Lost

Baby Lost