- Home

- Hannah Robert

Baby Lost Page 3

Baby Lost Read online

Page 3

‘Why was your kidney removed?’ He was genuinely interested. This was nice, but also a little bit worrying.

‘I had an ectopic ureter, so I kept getting recurrent kidney infections. I had surgery here,’ I reached around my still-big belly and touched a thin scar just above my pubic bone, ‘to fix where the ureter went into my bladder, and then they went to remove the damaged bit of my kidney.’ I touched my side, where a thick scar ran below my ribs. ‘But when they operated on my kidney, they accidentally hit an artery that wasn’t supposed to be there, and I lost a lot of blood. So they just took the whole kidney, and closed me up and did a blood transfusion.’

‘When was this?’

‘In 1983. I was seven.’

What I didn’t say was Please be careful operating on me.

Before they wheeled me into theatre, Jen asked if we wanted to pick an outfit and blanket for the baby. It still seemed very unreal. My sister had brought in a bag full of baby things that my mum had made or bought for Haloumi. My hand hovered between two blankets Mum had knitted. One was just too lovely to be cremated—I wanted to save it for a living baby (callously, I think now)—so I picked the other one.

•

There was no night on Sunday, 27 December. When I closed my eyes from the general anaesthetic, it felt as if only a moment had passed before I was opening them again; but this time, the weight and pain of my pregnant womb were gone. My fingers crept to my side—my belly felt soft, flat, bandaged. For a second I felt relief, and then remembered why I felt so much lighter. A face moved into my field of vision and came close enough to be less blurry. It was Jen. She handed me a photo. ‘You had a little girl.’

Everything else faded into background and all I could see was her—our daughter—with her round cheeks, dark hair and a pointy little Rima-chin. Our daughter, wrapped in the second-best blanket, which instantly became the best, most beautiful blanket for being wrapped around her. I couldn’t be stingy with my love now that she was born; I couldn’t hold off on loving my child because she was no longer alive.

3

Shavasana

We had one day with our baby daughter—Monday, 28 December. One day to name her, to give her a bath, to hold her and sniff her head and memorise every millimetre of her. People asked me questions while she was in my arms, but their voices sounded distant; I couldn’t look away from her face. She had a tiny bruise on her right eyebrow, lots of dark hair, big chubby cheeks, a serious, expressive mouth. I could imagine teenage attitude coming out of that mouth. I unfurled her little fist. A small, strong hand.

Before I had my own dead baby, I couldn’t imagine anything more macabre than a dead child. A dead baby was a plot device, pure metaphor, something frightening precisely because it was so unthinkable. But my dead baby, you would have loved her! On any objective scale, she was clearly the most beautiful baby girl ever born. She had a world-weary, uber-cool way about her. Not for her the corporeal indignities of living, screaming, pooing babies. Here she was, the mysterious one who’d been kicking me all along, now terminally mysterious and unknowable, yet so specifically herself. Birth is the ‘big reveal’ of motherhood, when a hypothetical, potentially generic baby becomes your own child. And yes, my heart split forever, with her part of it not setting off to walk around outside my body but heading for a stupidly small coffin and a private cremation.

My brother, Jeremy, arrived just as I was being prepared to be sent from ICU for another CT scan to check on the internal bleeding. He brought with him the soft grey rabbit he and his fiancée had given us for our baby at Christmas. I entrusted both rabbit and baby to my mum and the midwives, as the orderlies wheeled my bed out the door and towards the lifts. Jeremy took my hand, and stayed with me all the way down to the scanner. He is known for being the least chatty in a family of extreme chattiness. But there was nothing awkward about being quiet with him. I was reluctant to relinquish his hand when I was moved onto the bed of the scanner, but knowing he was there, solid and waiting for me as the machinery sent me into the tunnel of the CT scanner and out again, enabled me to breathe quietly. When I emerged, I took his hand again for the journey back to ICU—my new alien, but life-sustaining, universe.

•

On Christmas night, I’d driven to the airport with my sister and mum to pick up Jeremy. He was back from Germany because he’d been offered some lucrative rigging contracts. His German fiancée was having knee surgery and rehabilitation, but would soon follow him to Australia. We were staying at my dad and stepmum’s house over Christmas, before we moved into our new house after relocating from Sydney. I had missed my family so much in my seven years living in Sydney, and now it felt like things were gathering in again. We’d farewelled Jez early on Boxing Day morning when he caught a lift with a friend, heading down to work at the Falls Festival on the coast. He had hugged me, then ducked down to give my belly a quick peck. ‘See ya, Haloumi.’

•

‘Have you named her yet?’ more than one person asked me. I know they were being kind, but the question and being hurried irritated me. I couldn’t name her without Rima being there and, despite my pleading for her to be transferred, she was still in another hospital, being treated for broken ribs and a broken hand, and awaiting release.

‘Haloumi’ had worked well as our nickname for a growing, kicking bump, but the quiet baby girl in my arms needed a real name. We couldn’t keep referring to her as a type of cheese. In the busy weeks before the accident, in our preparations for Christmas and the move to Melbourne, Rima and I had chewed over the topic of baby names many times. We were settled on a boy’s name, but girls’ names were more difficult. We wanted an Arabic name, a connection to Rima’s Lebanese heritage, but so many of the names I loved provoked the response from Rima, ‘Oh, that? That’s an old lady’s name! We can’t call Haloumi that!’

At last, Rima appeared at the door of my ICU room, wearing her brother’s tracksuit pants and a hospital gown, her broken hand in a sling. She had discharged herself from the Alfred. I was holding our still-unnamed baby in my arms. ‘Rima, come meet your daughter,’ I said. ‘She looks like you, hayet—look at her chin.’ So much had happened since the ambulance officer had prised her hand out of mine so that he could remove her from the wreckage. All our haggling over baby names was irrelevant—here was our daughter and she needed us to name her.

Zainab was the first name that tumbled out of my mouth when I asked Rima what we should name her. It was one of the old-lady names we’d argued about, but now Rima said, ‘Yes, Zainab,’ without taking her eyes off our baby’s face. And I thought of our friend Izzy, the way she would squeeze us and say, ‘Kha-li-la!’ (my darling) like a Lebanese tayta (grandmother). It felt strange to declare her name, when she would never get to use it herself. But there she was, our Zainab Khalila. It was a big name for a small person, and particularly for one we knew so little about; so, often I would shorten it and think of her as little Z.

•

Shavasana. It’s a fancy yoga word for lying on the floor. It’s also called ‘corpse pose’, because imagining yourself as a corpse is a good way to relax every muscle in the body. When I started going to yoga classes a month or so after being released from hospital, the yoga teacher would introduce shavasana, and the tears would run sideways across my cheeks and make wet patches on the yoga mat near each of my ears. I would lie there, slack faced, heavy limbed, and think of little Z, her face soft with the absolute calm of death. Before our accident, I’d been safely insulated from death. It was something that mostly happened to old people, and corpses were horror-movie props.

Now, on the yoga mat, I would test out what it felt like to be dead, not in a melodramatic or suicidal way, but because it was so odd to be alive when I could feel so little continuity between my life ‘before’ and ‘after’. It was hard to shake the thought that maybe, somehow, I had in fact died in the accident, that maybe I was a ghost. Death had found its way into my body, had carried off its victim under my very ribs

, yet here I was, fraudulently breathing in and out. I was so alien to myself that I wondered if the old Hannah had died, and a new one had been born, like Venus, as a naked adult woman, appearing not on a shell from the ocean, but on an emergency-room trolley, the doctors and nurses around me like the four winds.

•

When I’d first held Zainab, she’d been warm. After Rima had come, after we’d bathed her, marvelled at her toes, dressed her in a small suit with brightly coloured stripes, I held her again and she was noticeably colder. We don’t have much time, little one, I thought. Did we put a nappy on her? It is a silly, small detail, but it bothers me that I can’t remember. The suit was soft, soft cotton and had little giraffe faces on the feet. At one stage, one of the midwives or social workers brought in a tiny pink dress with lace and bows—exactly the kind of thing we would never have picked for her. ‘Would this fit?’

We politely declined, but once the woman left, I was disparaging: ‘She may be dead, but we’re not dressing her in that.’ And we laughed the brittle laughter of the bereaved. I realised afterwards that it had probably been donated by a family who knew this feeling first hand, and I felt unaccountably mean for mocking their kind gift. Zainab, though, looked solemn; Nope, she wasn’t going to wear that, thanks! We felt wicked as we laughed. Guilty for allowing our faces to crack wide with laughter, disloyal for producing anything but tears. Still, it was a release—an emptying-out of the dark waters of grief, like weeping out loud together but without the fear that our sadness co-mingled would drown us.

Sometime after Rima got there, Jackie and Jazzie arrived. They had been discharged from the Children’s Hospital—Jazzie with a fractured hip, and a suspected fracture in her wrist; Jackie with a badly broken nose, stitches in her lip and mild concussion. Jackie had been sitting in the middle row of seats in our Nimbus, designed to fold down to give access to the third row of seats. In the impact, the seat had malfunctioned and folded, tilting her forwards, so that her face hit the back of my seat, or her own knees; we don’t know which. The ambulance had taken them to the Children’s Hospital as unaccompanied minors, while Rima and I had been sent to different hospitals. (Though, thanks to an extraordinary coincidence, the one and only person they knew who was employed at the Children’s Hospital—Charlie, a longstanding family friend—was on duty in the ER and ended up caring for them.) My stepmum, Debbie, got there as quickly as she could, and stayed with them all night. A week later, Jasmin presented me with a drawing she had done with her left hand (her right was in a cast) of her and Jackie in hospital beds, tears running down their faces, Debbie on a camp bed between them.

When they arrived in my ICU room, they were wearing blue scrubs from the Children’s Hospital, as their clothes had been cut off too. Jazzie was in a wheelchair; Jackie’s face was swollen from the impact, with surgical tape and gauze on her cut lip and broken nose. They had come to meet their baby sister. And to reunite us as the human contents of TAZ 012, together once more after being splintered apart across three different hospitals.

Here is our family portrait—me holding Zainab in the centre, Rima leaning in on one side, and Jazzie and Jackie leaning in on the other. Our faces were shiny with tears, swollen with bruises. My hair was a mass of blood-red Medusa coils. I was too bereft to remember to close my mouth or even to look properly at the camera, and Rima was unsure whether she was supposed to try to smile. Jazzie’s eyebrows were incredulous; Is this really happening? (This is not how she thought she’d meet her baby sister.) But Jackie’s gaze was level, direct, reproachful—not vindictive, but heavy with truth. This. This is what happened. I want the person who caused our accident to experience that gaze. Or, really, for every driver to see it as they lay their hands on a steering wheel.

Jazzie, then Jackie, cradled their little sister in their arms. It was difficult with a broken arm. We took a photo of Zainab surrounded by our clasped hands. Her lips had gone a dark red, as though she were wearing lipstick for newborns. ‘It’s the delicate skin on her lips drying out,’ a nurse explained. It meant she was looking less ‘sleeping newborn’ and more ‘funeral photo’. I loved her still, but I was glad we’d got some photos early on.

I am not religious, but in Rima’s faith, it was important to hold a funeral as quickly as possible. We planned something small. When Penny and I were in Year Nine at high school, Penny had confided in me that her mother, a hospital chaplain, often had to plan funerals for babies. As teenagers, we treated this as a weird horror-movie fact, remarkable mainly for the reaction it could elicit. I hadn’t considered what it felt like for the parents of those babies. I asked my dad to contact Penny and her mum, Judith, to ask for their help. I imagine it is very hard to write a eulogy for a baby who has died before she is born, but Judith did that for us.

Penny came and sat vigil in my ICU room. It was her hands, along with my mother’s and my sister’s, that helped Rima and me give Zainab her first and last bath. ICU only allowed immediate family to visit, so we told them she was my sister—and, in a way, it was true.

We had been inseparable as thirteen year olds, writing long notes to one another in class, borrowing lines and characters from our favourite movies, songs and books. We’d later stolen one another’s boyfriends and become estranged twice, but each time we reconnected through writing letters; a sorority in words that built a shared history bigger than any betrayal. In Year Ten, after I’d written something particularly angsty, my English teacher suggested I read Cat’s Eye by Margaret Atwood. ‘It’s one of the Year Twelve texts,’ she explained, ‘but I think you’ll like it.’ Somehow, it became a book whose storyline will always be entangled with my high school years, when both Penny and I read and re-read it, and with our friendship. Like Elaine and Cordelia in Cat’s Eye, Penny and I had lost each other for a while, but, unlike them, we found one another again and were kinder to one another than we had been as teenagers.

That night, Rima slept on two chairs pushed together next to my ICU bed. The next morning, she and my dad sat on the bed and I dictated a death notice for the paper. No one argued about the wording. I wondered aloud whether it should go in the ‘births’ or ‘deaths’ column, or both. Strictly, it was a double bill, and I wanted her birth and death acknowledged, but I conceded when Dad said the funeral home would probably just put it in the ‘deaths’ column.

To prepare for the funeral that afternoon, the ICU nurses tilted my bed so that my head was lowered, and washed the blood from my hair. Warm rivulets ran up my scalp, as though I were showering upside down. The nurses washed gently around the wound on the right side of my head. They rinsed all that bloody water from my hair and rinsed it again, then blow-dried it; not the way a hairdresser does, but the way you do getting ready for work in the morning. It wasn’t styled, but it was better than the Medusa coils.

My sister had been to see our car in the wrecker’s yard and to collect our belongings from it. There, folded neatly on the dashboard, were my glasses. In the chaos of the emergency department and the fog of the morphine, I hadn’t even realised they were missing. I was relieved to discover that the closed-in focus wasn’t just my shell-shocked brain but also my own ordinary short-sightedness. I was also reunited with my handbag—such an ordinary object, but it was something from before, and its familiarity made our new circumstances feel all the more alien. I opened my little mirrored compact to put on some make-up, fuzzily remembering my routine, usually undertaken on the train to Newcastle. First, the silvery grey eyeshadow along the lid line, then getting lighter from the outer corner. Then the pearly cream on the inner hollow and under the brow. Finally, a lip gloss. The mirror only afforded a view of small slots of my face, which was just as well.

For the first time since they had cut my clothes off me in emergency, I wore clothes rather than hospital linen. Rima had brought in the nightie the girls had given me for Christmas—soft cotton, with pink and green florals, and (as requested) buttons at the front that would be practical for breastfeeding a new baby. Per

haps a bit more nanna than my usual style, but beautiful because the girls had chosen it for me. Still, nighties weren’t quite funeral attire, even in these circumstances, so I needed something else over the top of it. My sister brought in a black top of hers and we stretched it gingerly over my head, cutting the waistband with scissors to get it over my post-partum belly.

I was to be transferred into a wheelchair with my broken leg raised in front of me. There was a moment of consternation when we realised the leg board I would sit on and that would support my broken left knee, held straight in a splint, was designed to support a right leg. A nurse was about to take it back and change it over, when we all realised, sheepishly, that it was the same on both sides; we just needed to flip it over and it could support a left leg.

A new ICU nurse—a young woman, Janelle, with a long, dark plait down her back—began her shift just as we were heading downstairs for Z’s funeral. She was a watchful guest, sitting in the last row of seats. Our other guest at the funeral was the Le Pine woman, who was going to take our daughter to be cremated. She waited patiently after the short service while we said our goodbyes. Being in the wheelchair, I couldn’t lean over to kiss Zainab, so I pulled the whole casket onto my lap and kissed her cool cheek, already wet with our tears. ‘This will have to do,’ I thought. This will have to suffice for all the child-care drop-offs, the first day at school, have-fun-at-camp goodbyes, airport-departure-lounge hugs—so many smaller farewells exchanged for this big one. ‘Please take care of her,’ I said to the Le Pine woman, and she squeezed my hand.

Afterwards, we sat in the hospital cafeteria. Numb. I drank real coffee, I chewed through a significant piece of cake, without tasting either. My sister came back to the table, and laid a black-and-white notebook in front of me with a pen. ‘Write,’ she said. ‘It’s what you do.’

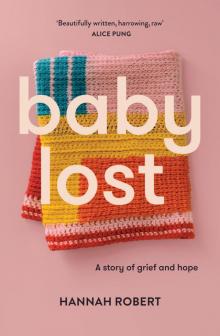

Baby Lost

Baby Lost