- Home

- Hannah Robert

Baby Lost Page 5

Baby Lost Read online

Page 5

During the day, I could hold onto the raft of family and friends and the distractions of food, doctors’ rounds and the physio or social worker. Nighttime was harder—it was just me and the big salty sorrow, with the beam of light from the night nurse swinging around slowly every so often. Pauline, the night nurse who had returned my Zimmer frame, often heard me weeping and came in to see if I was okay. She would pull up a chair and we would talk. One night, to try to calm me, she offered to rub my back. I rolled onto my tummy and with the fancy-smelling oil I had bought to rub into my stretch marks, she laid her hands on me and smoothed out some of my sadness, so that I could sleep for a little while.

Tuesday, 5 January 2010 1.10 a.m.

I don’t understand with all the buckets I am crying how I can also be peeing so much. There must be some great inland sea inside me. Perhaps when I move around you can hear me sloshing?

Oh I am in so much pain right now—a choir of pain, from the deep baritone ache of my knee to the sharp peaks of breathing with this broken chest bone. And over the top comes a weird melody of moans which I have never heard myself make before—a keening series of wavering ‘ahhs’ and alto ‘ohs’. I remember reading Shakespeare plays in high school and laughing with Penny at all the ‘Ah me!’ and ‘Alas!’ exclamations. But that was the luxuriously naïve laughter of someone who had not felt sorrow so visceral that it makes you cry out in pain.

And please don’t think that my analgesic needs are being neglected! Pauline and Pervin have just brought me my strong pain meds—signing them off in tandem as though I were a library book. No, I am being looked after well in that department—yet not too much, so I’m not living in a morphine fug.

No, while some of the other singers in this choir sing on the frequency of physical pain, most of them specialise in the other end of the spectrum—in sadness and madness. These are my two torture masters. They would quite like to drive me to a bad place of hurt and hate. They are taking me somewhere whether I like it or not, but I am pushing for a gentler destination—a silly puerile comic-grotesque direction in which people name their own legs. I know Alfred (left) and Hillary (right) are a bit old fashioned, but I really didn’t get a lot of time to think about it. One must make snap decisions sometimes and live with those decisions.

I need to find a type of crazy in which you can laugh at the most humiliating and revolting things, because this is the reality of my life right now—stinking out the room with farts that make even the flowers weep.

6

Frida and me

By day five, they wanted to send me home.

‘I have patients recovering from exactly the same knee surgery on the orthopaedic wards who are home already by day four,’ said the nurse manager.

I stared at her for a second. I hadn’t really comprehended that the rest of the world still existed beyond the hospital walls, let alone that I could be sent home.

‘But have those patients had caesareans too?’

‘Oh, I’ve had caesareans!’ By the time I formed the words to ask if her babies were born alive, she was gone, out of the room and off to manage the rest of the ward.

I started writing lists of the reasons why I couldn’t be discharged just yet:

• because I can’t get out of bed without assistance,

• because my partner is also injured and unable to care for me,

• because my able-bodied family members are already caring for my injured partner and two injured stepdaughters,

• because we don’t have a home to go ‘home’ to.

I still looked pregnant and I was scared that well-meaning people would say things that would inadvertently break my heart. I planned a little preventative sign to wear:

No, I’m not pregnant anymore.

My baby has died.

•

I dreamt of a broken bathtub, of roadkill bathmats, of a chandelier constructed from tiny, dried-out bats, like muscatel grapes. I dreamt that I was at Rima’s work, and was holding my yellow book with all my pregnancy medical records. Someone who didn’t know about the accident saw my Transport Accident Commission form, printed with two little human outlines on it where the doctors could indicate my injuries, front and back. She mistook it for an ultrasound scan.

‘Oh,’ she said. ‘You can see two of them in there—are you having twins?’ I wasn’t angry; I just cried, ‘No, no, no, I’ve lost my baby.’ Then someone offered to drive me home and I gave a scared moan: ‘No, no, no; I don’t want to go in a car.’

I dreamt that my hand was safe in my mum’s hand, strong and warm. With fingers interlocked, we stretched our fingers out—hers more wrinkled but so similar in size and shape to mine. As I turned our facing hands, I saw her ring, middle and little fingers on one hand had been amputated above the first knuckle. They were smoothly healed, and strong, but incomplete. I cried out, ‘Mama! What happened to your hand?’ She gave me a sad look. ‘Oh, that happened at work the other day.’ I want to shake her. Mama! No! No, this is not okay. Mama, you can’t let this happen to you. But she was right, it was too late to make a fuss. Nonetheless, I woke up crying. ‘Mama—no, no!’

I had a jungle of flowers growing from the top of the cupboard in my room, a bit like Max’s forest in Where the Wild Things Are.

•

Sunday, 3 January 2010 nearly 1 a.m.

I was telling Matt the truth when I said I was not even thinking about the driver who caused the accident. He’s an irrelevance to us now and to our recovery. What has happened has happened and getting angry at him will not change what we need to do to get better, and may make it harder.

I do remember that his name is Amrik—and so he must have a mother who brought him into the world, who held him and looked at his tiny face in wonder. And who gave him that name wishing only good things for him. I won’t judge him (not that that is my job or in my power in any case) because I have driven stupidly too at times.

I know that on the Wednesday before we moved to Melbourne, I drove so fast and so angrily with the girls in the car that they were scared—just because I was angry and frustrated and impatient with Rima and with some difficulty with the move, I can’t remember what. And Haloumi was in the car too, right there, below my angry heart, feeling all those stress chemicals circulate in my bloodstream. I thank God that the worst I did that day was upset my stepdaughters (that was bad enough) but I could have very easily caused an accident like the one which took our Khalila away. So, even if I can’t control other people’s driving, I promise never ever ever to drive when I’m that angry again.

I will stop the car, or not get into it, I will take a little walk or deep breaths, or smash plates, but I will not drive. I am scared to get in a car again—I will have to take that slowly.

•

My cousin Lou came to see me. We’d been to see her on the day of the accident. We’d kissed her goodbye at the gate, crossed the road to where our car was parked, pulled out from the kerb, turned left, then right, then left onto Warrigal Road, before being sucked into the black hole of the collision.

She hadn’t told her kids yet that our baby died. They had come in while she was on the phone to her mum, my Aunty Helen. They heard her weep. ‘Mummy, what’s wrong?’

I pictured her in that lovely new kitchen, leaning on the bench where my pregnant belly touched the stone, where we ate Greek biscuits before getting in the car. She went down on her knees, gathered their little living bodies close, one in each arm, sniffed into their necks.

‘There’s been a car crash. You know Hannah and Rima and Jackie and Jasmin, who came over yesterday? Their car crashed and they were hurt.’

‘Oh, Mummy!’ said Connor. ‘That baby must have been so scared.’

I hadn’t wanted to think of this. I want to think that she felt loved all the way through, that she felt the bang, but knew I was still there with her, even if I couldn’t protect her.

Tuesday, 5 January 2010 9 p.m.

Today was the day when everyone

thought I was going crazy. No wonder really, when I tell them I’m writing a blockbuster novel which is going to be made into a movie starring Charlize Theron (as me, obviously) and Salma Hayek (as Rima) (‘A heart-warming tale of tragedy, hope and incontinence’ or ‘Pollyanna on crack meets AB Facey’). Suddenly everyone was giving me worried looks—particularly when I insisted on writing down the names of every member of the hospital staff I met.

Here I was thinking that I had discovered a new post-accident Hannah with some inspiring new talents when everyone around me was thinking, ‘She’s dropped her bundle.’ What shocked me was when the person from Epworth Rehabilitation came to assess me for a transfer to the rehabilitation hospital. I immediately wrote his name down in the yellow book—Kamal. He made jokes about being born in the seventies, but when we got down to it, told me that their primary concern for me was my neuro-psychological state.

We still had a holiday house on the Mornington Peninsula booked for the two weeks before our tenants were to move out. It was meant to be our babymoon—our reward for making it through the big move and Christmas, a little rest before we unpacked our house and got set up for the baby to arrive. When the doctors did their rounds, I asked whether we could still go. I wanted to feel the salt water wash over me. I wanted to hide a bit longer from Melbourne and any idea of ‘normal’ life.

‘I don’t think it’s such a good idea,’ the doctor said. ‘This is the thing with internal bleeding—we take a three-three-three rule. For the first three days, there’s a significant risk of further internal bleeding—that’s why we kept you in ICU. For the next three weeks, the risk is reduced, but it’s still quite serious. The risk reduces again after three weeks, but you’ve still got a higher-than-average risk of bleeding for the next three months.’

‘How would I know if I was bleeding again? Would it hurt?’

‘Not always. You can bleed to death without feeling much at all.’

A different nurse manager came to see me. His name was Ali. He admired the letter Jasmin had written to me, left-handed, as her right hand was still in a cast.

Dear Hannah

I’m so happy that your happy (ish) but just know that I’m here for you like how you were those past few years but yeah so is everyone else. I was so happy that I got to see you yesterday but yeah sorry I’m writing in my left hand!! My hand doesn’t smell much anymore!! But it hurts. I love you see you chao from: Jasmin

He Blu-tacked it to the wall for me. ‘I need to ask you a favour. We’re looking at transferring you to rehab, but we’ve got a bit of an issue with rooms. Can I ask you to change to a shared room, just down the hall?’

I was grateful for any reprieve. My mum helped me pack up my things, piling bags and belongings on the bed, with me holding the vases of flowers. The photo the midwife gave me of Z was now in a glass frame Mum had bought from the hospital gift shop. I wrapped it carefully in her blankets, first one and then the other, and hugged it to my chest. The nurse released the brakes on the bed, and pushed us out of the room and down the hallway, like a little boat. Suddenly I felt the urge to document this. ‘Mama, do you have your camera? Can we take some photos?’

The image of the bed piled with notebooks, colourful blankets and flowers, reminded me of Frida Kahlo, the surrealist artist I had been obsessed with as a teenager. When she was eighteen, Frida was on a bus on her way home to Coyoacán, Mexico City when it collided with a trolley car. She was thrown from the bus—and in the process was impaled on a handrail from the bus, which pierced her lower hip and came out her vagina. The impact fractured her pelvis, and broke her spine in three places, as well as her collarbone, two ribs and her right leg and foot. She was immobilised in a cast for a month, and underwent over thirty-five operations.1 Frida’s life, too, was pierced through with the after-effects of the accident—her health, her fertility (her injuries meant she was unable to carry a pregnancy to term) and her artwork.

Prior to the accident, she had ambitions to become a doctor, but ‘bored as hell’ in a hospital bed, she began painting. During her frequent convalescences she would often decorate her bed and the spinal casts or orthopaedic corsets she had to wear. Stuck in hospital or in bed, her portraits were primarily self-portraits—her gaze, level and direct, her brows, serious and meeting in the middle like a pair of raven’s wings. Her portraiture was realist, down to the fine black hairs on her upper lip, but she interwove or surrounded her portraits with more surreal scenes. Frida’s face appeared on the body of a deer, or suckling from a Pre-Columbian statute, or surrounded by flowers and monkeys. This was exactly what I wanted—to meet the horrors and indignities head-on, to examine them, and myself, and somehow to find beauty without smoothing out the painful parts or finding neat answers for unanswerable questions.

I had been at a loss as to how to understand myself as injured and grieving while still maintaining some measure of dignity. So I took Frida as my patron saint, as my survival mentor, as inspiration to look my circumstances directly in the eye and to document my pain with an artist’s curiosity. My life in Frida-vision suddenly seemed artistically surreal rather than dangerously crazy.

In the new room, I felt the need to keep the rails on the bed up, as though this bed-boat that had carried me here might at any moment lurch and roll, bellied by a big dark ocean. I drew a ship in my notebook, with Z as the anchor, and wrote the words of another Little Birdy song on the sail.

Who’s going to love you now, baby?

Who’s going to love you now, baby?

When you’re done fighting that war at sea

Get on that ship and sail back to me!

Penny came to visit again. She climbed up onto the bed with me, and I showed her the ship drawing and together we wept.

I called my mum and wept again. ‘Mama, I just need to stop for a minute. I need to stop and wipe the phone because I’m crying so much that I’m scared I’ll electrocute myself.’ This, for me, counted as a good laugh—that and announcements over the PA system about returning the bladder scanner to level five—and for a little while, I shook with both tears and laughter. ‘Mama, I’m not a person at all, I’m just a force of nature,’ I said. I pictured the Pasha Bulker, the container ship washed up on Nobbys Beach in Newcastle in the big storm of June 2007. On our way north for a hockey carnival, we had stayed the night in an onsite van at a Newcastle motel, feeling the storm shake the thin walls. We woke and drove into town, passing cars made flotsam by the floods, with high-tide marks of dirt and leaves reaching their windows. And there on the beach, tall as an eight-storey building, was the Pasha Bulker, the surf lapping it, but dwarfing the beach pavilions, and commanding an audience of surprised-looking adults and kids still in pyjamas.

My hysterical laughter slowed to sobs. ‘Mama, I don’t know how I’m going to sleep.’

On the other end of the phone, my mum spoke softly. ‘When I was in the Alfred and had trouble sleeping, the women there gave me something to say which I could repeat to make myself feel safe and calm.’

She meant the psych unit at the Alfred Hospital, where she had spent uncounted weeks in late 1987 after a particularly bad bout of depression. This was not a usual topic of conversation for her.

My brother and I had been in primary school, and while Mum was in hospital, our art teacher, Miss Komis, would drive us home from school. ‘Call me Fifi,’ she said, and sometimes took us out for ice-creams on the way home, as a treat. I would sit in the front passenger seat of her cobalt-blue car, touching my finger to each unfamiliar object: the perforated leather of the door handle, the chrome door latch, the glove box. The more practical details of that time are fuzzy. How long was Mum in hospital for? Who looked after our little sister, who was not at school yet? But I clearly remember the piles of cicada shells my brother and I collected each afternoon after Fifi dropped us home, and the vinyl chairs in the hospital’s TV room when we visited. Everything was hushed there, and Mum was even quieter than she’d been in the weeks leading up to her hospitalisa

tion. She looked half-transparent, as though she had lost the will to be seen. At home, I was a bossy, responsible big sister. I helped Dad cook dinner and do the shopping, and I referred to my brother and sister, five and seven years younger than me, as ‘the littlies’.

‘The phrase they gave me,’ Mum continued, ‘was, “I wrap this pure white cloak around me through which nothing can harm me and only goodness may pass”.’

I repeated it back to Mum several times. I liked the idea of a cloak filtering out harm, permeable only to goodness. But I wasn’t convinced that anything could protect me, or those I loved, anymore.

I was conscious that, now that I was sharing, I shouldn’t keep my poor roommate awake, but I couldn’t figure out how to stop the weeping and laughing and writing. I asked the nurses again whether I could see a counsellor. Several hours later, a volunteer arrived. Just as well—on one of my many lists for the day, I’d written, ‘If no psych assessment by 5pm, DRAW ON MONOBROW.’

Pat was older, quietly spoken and wore a smart suit with a brooch. She wasn’t sure whether she could help, but encouraged me onto my crutches and out into the hallway, further than I’d been in my whole time there. Pushing back the boundaries of the known universe, we found a corner with two chairs, and she patted my arm. We formulated a plan that didn’t involve weeping all night and she walked me back to the ward. I pulled up the sides on the bed, invoked Frida, covered myself with hand-knitted baby blankets, pushed the ivory bangle up my arm and set sail for the night.

7

Tabloid tragedy

My sister let slip that there was a story about us in the paper. I could always trust her not to filter information for me.

I asked for a copy and Rima obliged, buying one from the hospital newsagency and bringing it up to the ward. I wasn’t prepared for it to be the front-page headline. Our story wasn’t just our story anymore; suddenly, it was a ‘tragedy’, for people to tut over on their tea break. Part of me felt vindicated. I wanted our loss to be important—everyone should know we had lost our baby daughter. How could anything hurt this much and not be front-page news?

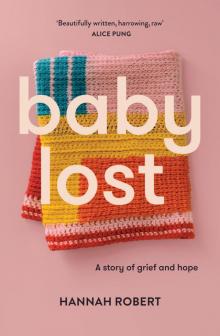

Baby Lost

Baby Lost