- Home

- Hannah Robert

Baby Lost Page 6

Baby Lost Read online

Page 6

But it also felt very odd to have everything that had happened to us in the past days reduced to twelve characters of thick black headline. They had also got it wrong. ‘LOST IVF ANGEL’. She wasn’t IVF conceived. And Rima was not, as was reported, my sister-in-law. I felt ill at ease. I was conscious that the pedestal for tragic, wronged mothers is a narrow and unsteady one, surrounded by a sea of condemnation for ‘bad’ mothers. I knew from growing up with seeing Lindy Chamberlain on the television that it all could turn very quickly. I didn’t have an unusual religion; I had the benefit of white, middle-class privilege; and now the Herald Sun had incorrectly extended me the benefits of presumed heterosexuality. Did I really want to poke that bear?

When I had a gap between visitors at lunchtime, I called the Herald Sun news desk and asked to speak to the journalist: ‘The front-page story from today is about me, and it contains factual errors. I want a correction published.’ They put me through to the journalist, and when I told him off for his inaccuracies, he was contrite, and wanted to make it right.

‘I’ll do better than a correction,’ he said. ‘I can do another story.’

Suddenly he seemed a little too eager to put it right—and he was offering to come in and talk to me. ‘I need to think about this,’ I said. I gave him Mum’s phone number, deliberately creating a buffer zone.

When I told family members I’d been in touch with a journalist, there was some alarm, particularly given my recent crazy-lady antics. Apparently, a journalist had turned up at my dad’s house, pressing him for comment, and my dad and stepmum had had to keep the phone off the hook. Over the next few days, I consulted with my friend Matt, a journo, about what to do.

In the meantime, I had to pack. I was being transferred to a rehabilitation hospital. I was triumphant about not being sent home yet. Mum helped me shower. It was complicated. I covered my left leg, splint and all, in a garbage bag, propped it on one chair and sat on another. Mum left to let me dry myself and start getting dressed. I took my time. There was a lot to look at, seeing my body naked.

Black and dark purple bruises blossomed, like tropical botanical illustrations, from my elbows to my fingertips, cascaded down my thighs, and nestled, deepest of all, in a seatbelt stripe across my chest. The dark, dead blood collected in strange patterns—sheet marks, the creases of my wrist, the waffle pattern of a wound dressing, in the lines of the old scar from my kidney operation. This was a kind of bodily print-making practice. My left breast hung heavy, covered in one big bruise that faded to yellow at my cleavage.

When Rima came in, I had a new favour to ask her. ‘Can you take photos of all the bruises? They’ll disappear soon—I need to remember this.’ She was systematic about it, starting with my feet and working her way up. ‘There’s one behind your right ear; maybe from your glasses?’ I posed, pointing to the bruises, like the saints in Renaissance paintings touching their wounds. Look. Here. Proof. What did it mean, to photograph this naked, bruised body? Was it pornography? Crime-scene photography? Art? I didn’t know what to do with my face in these photos. Sometimes I smiled. Sometimes I looked away.

To catch the full colours of the bruising, I had to hold my arms out in front of me, hands up. When Rima showed me the photos, I saw a woman trying to defend herself.

When the nurses came to change the dressings, I got the camera out. I wanted to see what was under all those patches. This body, which had been mine for thirty-three years, was unfamiliar to me. On my right ankle, two staples held shut a small but deep incision, alongside a U-shaped cut. In the fleshy bit of my forearm, a small wound was still weeping where they had pulled out a long shard of glass. Several big dressings covered my left knee, and I could feel the staples underneath making three quarters of a circle around the knee cap. The surgeon had joked that I’d have a hammer and sickle scar. My communist left leg. Ha ha. Rima took fuzzy photos of the lumpy scar on my head—pink, and still stitched with thick black thread.

As systematic as Rima’s photos were, they were not enough. I borrowed my mum’s camera, and shut myself in the bathroom. My supply of Rima’s t-shirts had run out, so I had been wearing two hospital gowns, one on forwards and one on backwards, to avoid the unflattering gap. It was the sartorial equivalent of a kidney dish—without my own clothes, jewellery or make-up, and in the starkness of the hospital bathroom, my body looked like a medical specimen.

The morning of my transfer, I picked out a kaftan-like green and white dress from the bag of Mum’s clothes she had brought in for me so I didn’t need to wear my maternity clothes. I tied the hot pink belt from my dressing gown above my still-big post-partum belly. I tied my hair back and put on make-up. I held Mum’s ivory bangle to my lips, inhaling its smell and invoking the elephant whose life was claimed in making it. Elephant—I’m so sorry. Please haunt me, please protect my baby girl, wherever she is. I sticky-taped a sign to my belly: ‘I’m not pregnant anymore. My baby has died.’ I knew it was unlikely that anyone would comment, but the thought that people might see me and think I was still pregnant was unbearable. I needed to open a window on this stifling pain, let others peer in.

•

The week before we’d come down to Melbourne for Christmas, Mum had stayed with us in Sydney and we’d gone shopping in Newtown. In a small shop full of beautiful things, she had bought an oval enamel brooch with a matryoshka face on it, like a little doll. At the time, I’d felt covetous. It was a beautiful, expensive object, exactly the kind of thing I couldn’t justify buying when we were relocating interstate and about to have a baby. But the matryoshka brooch reappeared while I was in the trauma unit, Mum slipping it wordlessly into my hand. The enamel was solid yet silky-soft, and the small baby face, with a blue asterisk on each cheek, smiled at me. In the shop, it had just looked cute and smiley. Now I assumed the asterisks were tears. I pushed the pin through my clothes, and then through my bra, so I could feel the cool metal of the clasp against my breast, always on the left side, over my heart. Here you are, my little one.

•

When the orderlies arrived to transfer me by ambulance, I was chipper. ‘We’re working on the theory that you’re taking me to rehab in a hovercraft,’ I said. ‘So it can just float up and out of the way of any accident. Does that sound okay?’ They were reassuring. They thought I was having a joke with them.

Mum came with me. I held her hand as the trolley clicked into place and the doors were closed. I blinked slowly as we emerged into daylight and the world beyond my hospital bubble. Through the venetian blinds of the ambulance, I could see streets, trees, traffic, all behaving as though nothing had happened. This time we travelled without the sirens. This time, the outcome was known. There was no great rush.

•

In my room in the rehab hospital, I met the nurses and told my story. Then the doctor, then the physio; lunch; then the psychologist, the occupational therapist, and the other doctor. By 5 p.m., I had told our accident six times over, and by the time Rima arrived, my compliance was gone. Everything felt wrong, and suddenly I was white-hot with anger—at this stupid hospital, at the other driver, at myself for thinking this was all somehow fixable if only I behaved correctly, at Mum and Rima for being there and not being able to fix any of it. I was contrary, inconsolable. The air-conditioning was on too high, the mattress was too soft and I missed the nurses from Royal Melbourne. Mum and Rima didn’t know what to do. Take photos, I told them, and then I gave them the finger when they did. I was sorry, though, when visiting hours were over, and they had to go, so that it was just me and the photos of Z in my new room. I stayed up late drawing a diagram of myself, with arrows explaining my injuries and my family relationships, to be stuck onto the door of my room so that I wouldn’t need to explain it all to anyone else.

At 7 a.m. my phone buzzed with a text message. It was from my friend Kana, announcing the safe arrival of her baby girl. I wept, and plucked tissue after tissue from the box on the nightstand, with the ‘robot arm’ the occupational therapist had giv

en me, just to hear the tearing sound they made as they came out of the box. The information echoed around my heart like a loose spanner in an empty toolbox. I logged onto Facebook for the pictures. Here were the photos of Kana and me at her baby shower only a few weeks ago, standing belly to belly. And here was her baby daughter, alive and safe in her arms; my baby, dust. I wrote my own Facebook post.

7 January 2010

What happened is still so raw and new that we are wrapping our heads around a new bit of it every day. And also failing to wrap our heads around, and howling at that failure and our loss and the fact that our daughter will never open her beautiful eyes to see the people who love her more than anything. An inaccurate version of what happened was on the front cover of a tabloid newspaper. This is my response to it:

Letter to the Editor

Eleven days ago I was 34 weeks pregnant and driving home with my defacto wife in the passenger seat and my beloved stepdaughters in the back seat. A four-wheel drive came onto our side of the road and hit us. We were all badly hurt but our baby daughter died in my womb from the impact. My defacto wife (I can’t call her my wife because in this country we cannot marry) and I had spent nearly four years getting to know our sperm donor, undertaking tests and trying to get me pregnant using assisted conception (fortunately we did not need IVF). When the Herald Sun reported the accident and our loss on 28 December 2009, (‘LOST IVF ANGEL’), it mistakenly called her my ‘sister-in-law’ and referred to my stepdaughters vaguely as ‘two children’. Many people reading your article must have been wondering about the relationships between a pregnant woman, her sister-in-law and these two children who were all hurt in the one car. I just need to clarify—we are a family. My defacto wife (what a clunky phrase that is) and I lost our little girl, and our big girls lost their baby sister. I don’t want our family to be invisible—we have enough pain and injuries to deal with at the moment.

But in this strange movie which is apparently now my life, the most genuine and real thing is the love we have felt around us from family, friends, and also people who may not know us in real life but have very real compassion for us (or worse, have been through equally heartbreaking things themselves). It is huge, and we feel so warmed by your love but at the moment we are still so broken—physically, and in our hearts, that we can’t respond to all the messages. I am out of ICU (yay), out of the trauma ward (yay), and in rehab. I hate being here—but am doing my best to heal and learn how to do basic things so I can get home and be with my beautiful girls and do the rest of my healing there. Rima & girls are out of hospital (yay), but there are still various stages to go.

We will never ever be the same after this. I could never have imagined that the Haloumi who kicked and hiccuped inside me could be such a beautiful little baby girl. If the impact had not abrupted the placenta she would have been fine and things would be so different. I am so proud of her and so so heart-broken. Thank you for your thoughts and love.

We will be having a 40 days memorial at some stage—possibly early Feb when she was due. Forty days is significant within Rima’s faith. For forty days the soul wrestles with itself and its good and bad deeds in the desert, before moving on (though we’re pretty sure our girl didn’t have a bad deed to her name). If you are able to join us, we would love it so much. I warn you it is going to be very sad. We will have a weeping competition and I will win. The pay-off is you will get to see pictures of the most beautiful grumpy baby girl in the world.

•

One morning in rehab, I had a phone call from the police officer handling our case. He’d spoken to a number of witnesses and it was clear that it hadn’t been the Pajero driver’s fault at all. The collision had started, he said, with an older-model Commodore, whose driver was involved in some kind of road-rage altercation with another car. Several kilometres back, the Commodore driver, a uni student, had slowed down and stopped in a no-stopping zone to drop off a friend. The driver behind objected, hooted his horn, overtook the Commodore in an aggressive way, and was seen shaking his fist and yelling at the Commodore driver. In response, the Commodore driver sped up and tried to overtake aggressively in turn, but he didn’t get the chance to yell anything, because he didn’t check his blindspot when overtaking and failed to see the Pajero in the next lane. The flanks of the two cars made contact, knocking the Pajero onto our side of the road.

It took me a few moments to process this news. The Pajero driver was not at fault. His car was just a big, heavy billiard ball tapped in our direction.

In the aftermath of the collision, witnesses saw the Commodore slow down and pull over briefly, but while other drivers around us were stopping to render assistance, the Commodore driver drove off, and returned the car to his brother’s house. When the police traced the car’s number plate to that address and arrested him, he told them he had fled the scene of the accident because he was fearful of the other driver involved in the road-rage incident. He was charged with five counts of dangerous driving causing serious injury (one each for me, Rima, Jasmin, Jackie and for the driver of the Pajero) and one count of failing to stop at the scene of an accident, and was released on bail. Because she was stillborn, there was no charge for dangerous driving causing Z’s death. ‘Serious injury’ didn’t come close to describing our loss, but I was okay with her coming under my jurisdiction rather than that of the Crimes Act.

I sent my letter to the journalist, and, as promised, he spun it into another front-page story. I sticky-taped the front page to my door in rehab, with a drawn-in apostrophe correcting it from ‘Mum’s Pain’ to ‘Mums’ Pain’. The article also reported on the bail application, at which the police prosecutor argued there was a risk the defendant would try to leave the country while on bail, citing the example of another Indian student, Puneet Puneet, who fled in June 2009 after pleading guilty to culpable driving causing death and negligently causing serious injury.

Bail was granted but, nonetheless, our case fed into the mounting tension between the Victoria Police and the Indian community in Melbourne, over perceptions that police were failing to respond adequately to a spike in violence and race hate incidents against Indian people. A string of murders and assaults on Indians in Melbourne through 2008 and 2009 had prompted the Indian government to issue a travel warning for citizens considering studying in Australia, and sparked protests in Melbourne and New Delhi. In this climate, many journalists described the driver who caused our accident not as ‘a student’ but as ‘an Indian national’. I had a queasy feeling as I realised that our story played neatly into racist stereotypes of a white woman (and, worse still, a pregnant one) harmed by a brown man.

•

Each day in rehab, I was booked to work with the physio for an hour or two. I would go on my crutches down the corridor and to the ‘gym’, which was less like a gym and more like a surrealist kindergarten. There was play equipment for adults, parallel ballet barres, a play kitchen, and a rail with clothes hanging on it (dress-ups?), along with fit balls and yoga mats. And then there was the thing I averted my eyes from. I knew it was there because I had seen it the first time I walked into the gym and felt a jolt of fear through my gut. A weepy, elongated sigh escaped from me. I knew that, at some point, the physio would move me towards it. It was a dismembered car—just the front half, so that you could practise getting in and out of it on either the driver or passenger sides. As the physio taught me how to tackle stairs on crutches, I arranged my ascent and descent so that I didn’t have to look in that direction. The steps led up to a clothes line, and with each ascent I triumphantly moved a peg from one line to the other, with an absurdist flourish.

To add to the surrealist effect, one day I arrived in the gym to find my Year Twelve English teacher there, also being coached by a physio. We were like racehorses, being nudged along by our minders. We couldn’t chat properly but I got enough of my story out for her to get it.

‘I hope you’re writing, Hannah.’

I assured her I was, and she made me memoris

e her email address so that I could write to her.

8

Permission to bend

The accident, and the long hours that followed of ambulance, emergency room, labour and then waking from surgery to see our daughter, had obliterated the normal markers of daytime, nighttime or mealtimes. Time started again from zero—everything was measured in hours, and then days, since the accident. In rehab, I started reconnecting myself with ‘outside’ time, looking at the newspaper each day and marvelling that people’s lives went on regardless of our catastrophe.

One of the elephants at Melbourne Zoo was due to give birth to a calf any day now, and I followed the story, terrified that her baby too might die. The article recounted a statistic that made my heart ache for elephant mothers. For elephants giving birth in captivity, there was an extraordinarily high stillbirth rate, particularly for first babies. I thought of mother elephant eyes, weary with sorrow, and of a mother elephant trunk, searching out and touching on the still, hairy form of her baby, and wept my own elephant tears.

While I was eating my breakfast one morning, I drew rows of wonky boxes in my diary so that I could count the days. It was a double calendar. Each box had two numbers: the date and how many days since our own ground zero. Just writing the number ‘27’—the date of the accident—made me shudder and cry. I dripped strawberry jam on that box and drew a sad face beneath. It didn’t quite capture the violence of that day, but I couldn’t leave it unmarked. I’d had plans for these dates. These were to be days in a rented holiday house, lazy walks to and from the beach, with time to decide on a name for this baby, and to recover from the interstate move before we moved into our house and set up a nursery. By numbering those boxes, by stitching together these beautiful summer dates with our new messed-up reality, I inserted myself back into time, and was no longer in the suspended, timeless world of hospital.

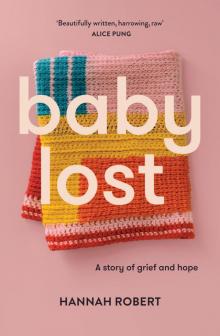

Baby Lost

Baby Lost